Stop me if you’ve heard this one before. A 20-something Black and Puerto Rican college student walks into a Halloween party in the late 2000s. All of a sudden, he hears the voice of a close friend from across the room. He doesn’t see their face but sees they’re wearing normal clothes. The twenty-something Black and Puerto Rican college student walks up behind their friend and says “Who are you supposed to be?” The friend turns around—and reveals they’re wearing blackface. With a smile, the friend says to the 20-something Black and Puerto Rican college student, “I’m you.”

Unfortunately, the scenario I described is not an edgy opening bit for my future Netflix comedy special. It’s something that happened to me at a Halloween event some years ago. I hadn’t thought about that stomach-churning night until I saw a headline about 30 Rock a few weeks ago. Tina Fey, along with the show’s co-creator Robert Carlock, announced that she wanted to address the instances of blackface within the comedy series. She issued an apology and pledged to remove certain episodes from the series on various streaming platforms. Fey would make these scenes disappear.

As I watched other creators follow Fey’s lead, the memory of that Halloween night kept haunting me like a really, really offensive ghost. And I knew why. It’s because I know something that Fey and all those creators didn’t know about addressing the pain of blackface in your past:

Making it disappear doesn’t work.

My college friend, on one hand, and this Emmy Award-winning comedy show on the other did more than just use offensive makeup for a quick laugh. When they put on blackface, they continued a practice that has deep and ugly roots in American culture. Before I can fully explain why making it disappear isn’t the best way to solve the problem, I have to explain what this offensive practice is, where it came from, and why it hurts. Along the way, I’ll be pointing out some not-so-great examples from American media. While the majority of my references won’t be taken from the sci-fi and fantasy content that you would normally see on Tor.com, I think it’s still important to tackle this issue, which is larger than any one genre or fandom, at this moment in time. Fully addressing the problem of blackface and facing the damage it has caused is just as vital to genre movies and franchises like Star Wars, the Marvel Cinematic Universe, or Shrek as it is to mainstream sitcoms, movies, and entertainment…and beyond that, to real life.

It might be helpful to begin with the dictionary definition of blackface—bear with me, here. According to Merriam-Webster, blackface is defined as “dark makeup worn (as by a performer in a minstrel show) in a caricature of the appearance of a Black person.” Now, what stuck out to me most about this definition is that it doesn’t discuss intent in any way.

The dictionary doesn’t ask why a person chose to put on racial makeup. Its definition also doesn’t distinguish between a person trying to imitate an African-American person or, say, a dark elf (but more on that later). According to the official dictionary definition, as soon as a performer—or a friend—chooses to alter their appearance by imitating or exaggerating the features of a Black person, they are doing blackface.

The widespread practice of using blackface in America began in the 19th century, when a type of performance known as the minstrel show became popular in America. The shows featured actors wearing blackface while playing stereotyped African-American characters. To say that these depictions were insulting would be the understatement of multiple centuries.

Blackface performers typically portrayed African-Americans as unintelligent, oversexualized, and happy with life under slavery. These actors continued to perform and promote these shows while Black people struggled to get basic rights in America, continuing on in the decades after slavery ended, through the turn of the century, and into the early days of film. How could Black people ever hope to change public perception of themselves if one of the most prominent ways of representing their race in America was an insult on every level?

As the 20th century went on, live minstrel shows thankfully began to close their doors permanently. Yet the tradition of blackface stayed alive and well in Hollywood. The infamous Birth of a Nation used blackface to portray Black people as stupid, bestial, violent, and menacing in 1915. In 1927, The Jazz Singer, the film that launched the sound era with synchronous singing and spoken dialogue, made blackface performance central to its plot. There was a Looney Tunes cartoon called Fresh Hare that put Bugs Bunny and Elmer Fudd in blackface makeup in 1942. And on and on… even decades later, in 1986, an entire movie devoted to a white actor pretending to be Black was released under the title Soul Man, becoming a box office success.

I could go on chronicling the depressingly long list of movies and TV that feature blackface, both before and after 1986. I could also discuss instances of yellowface in movies like Breakfast at Tiffany’s or the brownface in West Side Story. And I haven’t even touched the instances of blackface in American theater—but, to be honest with you, I think we’ve all seen enough to prove the point.

Although the racist minstrel shows that had originally made blackface popular had virtually disappeared, the American entertainment industry was still keeping the painful tradition alive. It was as if blackface was a virus that found itself permanently embedded in the body of the entertainment industry. Just when you think it’s finally gone with the new millennium, you see it pop up on 30 Rock, or in a Christmas episode of The Office in 2012. Or smiling at you in the middle of a Halloween party.

Almost a century after the heyday of minstrel shows, creators are stepping forward to stand against blackface in their works. In the era of Black Lives Matter and intersectionality and calls for better representation, they are willing to confront a tradition that is rooted in racism and holds painful associations for people of color. These creators will finally address the use of blackface by…pretending it didn’t happen?

In June of 2020, Tina Fey announced that four episodes of 30 Rock would be removed from streaming and rerun rotation because they featured actors in blackface. Bill Lawrence, the creator of Scrubs, requested that three episodes of the series be taken down for the same reason. Over on FX, five episodes of It’s Always In Sunny in Philadelphia were removed from streaming because they all featured scenes of main characters putting on blackface.

This disappearing act even affected shows that seemed like they might escape the recent scrutiny. In the second season episode of Community “Advanced Dungeons & Dragons,” an Asian character named Ben Chang dresses up as a “dark elf.” He chooses to embody this character by painting his exposed skin jet black.

Although Chang wasn’t directly parodying a Black person, the makeup he used for his skin could be considered “a caricature of the appearance of a Black person.” Since Chang’s actions fit the dictionary definition of blackface, Hulu and Netflix pulled the entire episode it appeared in. But I was still left with questions.

Where do these removed episodes go? Are they going to be locked in a Disney vault with Song of the South? Will the original DVD copies of these episodes be launched into space like Elon musk’s Tesla? Can we bury them in the desert like all those E.T. Atari game cartridges? After composing a dozen other pop culture-appropriate scenarios for how to get rid of these episodes, I realized that it doesn’t matter how deep they are buried. These creators could discard these episodes and let the series stand as if nothing happened. If someone started watching 30 Rock or It’s Always Sunny for the first time today, they would have no idea that the series employed blackface during their runs. The creators no longer have to confront or justify their past decisions to use racist makeup. Now that they have acknowledged using blackface and removed the examples, they can simply continue on, moving onto other projects with ease.

But it’s not that easy for me. As I watched creators scramble to make these episodes disappear, I knew it wouldn’t be enough. I know that because I tried to do the same thing.

The night my friend wore blackface, I felt these giant waves of shock and disappointment churning inside of me. At the same time, a dozen questions raced through my mind. How could this person do this? Didn’t they know what blackface is? Are they ignorant of the practice or are they ra—

I didn’t want to face their blackface. I wanted badly to pretend that my normal night wasn’t scarred by a painful and insulting act. So I did my rounds and said hello and made Halloween puns to everyone I saw before heading home. My friend left separately. While they were able to go home and wipe off the makeup, I couldn’t shake the bad feelings from the night as easily.

In the days, months, and years that followed, I spent a lot of time getting rid of every reminder of that party. I untagged myself from pictures, unfollowed people who posted about the party, and resolved to never talk to my friend about their choice to wear blackface. I thought this was enough.

But then we fast forward to 2020. In the wake of a surge of Black Lives Matter protests and raised awareness surrounding issues of racial justice, some individual American creators took stock and decided action was needed. When they announced they would address the issue of blackface in their work by making it disappear, my stomach started churning in an all-too-familiar way. I felt exactly like I had on that Halloween night. Suddenly, I realized that making the images of blackface disappear from my life hadn’t made me feel better. I needed to confront the situation. I needed to have a conversation with an old friend.

As I prepared for the most potentially awkward text exchange of my life, I began to notice that there were creators in Hollywood that were willing to have honest conversations about their pasts, too.

The studio behind the critically acclaimed Mad Men recently made headlines for deciding not to remove a 2009 episode that featured blackface from streaming services. If you’re unfamiliar with this show, it basically revolves around a bunch of guys and gals smoking and drinking throughout every day of the 1960s. (I think they occasionally work too, but I digress…) In one episode, an executive named Roger Sterling (played by John Slattery) appears in blackface at a party he’s hosting, singing to his new bride. This was supposed to be, *checks notes*, both funny and romantic?

The showrunners have committed to presenting this offensive moment in its entirety. Before the episode starts, the show will add a disclaimer explaining why the character thought it was appropriate to do and why the creators chose to display it. At the same time, they will openly acknowledge how disturbing and painful this tradition is. They want to be honest with their audience about the choice they made to use blackface.

HBO Max adopted a similar strategy for Gone with the Wind. Although the movie doesn’t contain instances of blackface, the story promoted offensive Black stereotypes while trivializing slavery. Within the movie, slaves are depicted as being happy and contented with their situation while their hardships are ignored. After removing the movie for a few weeks, HBO Max brought Gone with the Wind back, repackaged with a new introduction.

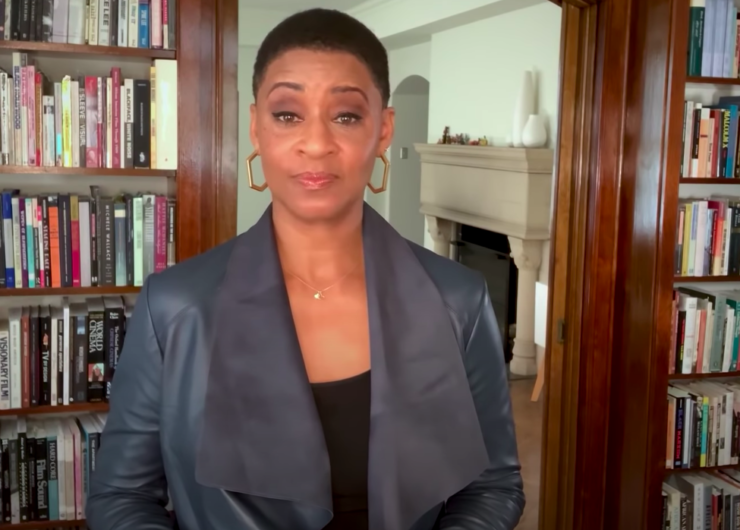

When the movie starts, viewers will watch a 5-minute and 40-second video from Jacqueline Stewart, a Black professor of cinema studies, as she breaks down how the movie glosses over and misrepresents the horrors of slavery. Stewart notes that the movie was protested for its offensive subject matter when it was originally released in 1939. Her introduction also explains how the Black cast members weren’t even allowed to sit with the white cast members when the movie was nominated for several Oscars. After she lays out this context, the movie itself begins.

Mad Men could have omitted its offensive material, and HBO Max could have simply pulled the film, and just moved on. But they took an important extra step: they chose to address and contextualize their problematic stories and open them up to further discussion. Their apologies aren’t quick PR statements that can get lost in the social media shuffle. The statements and explanations that these creators added will become part of a larger conversation, and hopefully lead to a deeper understanding of both the past and the importance of better representation going forward.

Even if someone tries to skip the intro and go straight to the film, they know what’s being skipped. Audiences can’t ignore that something about the art they consume has changed. These creators have called out the issues in their own stories to encourage people to think about the issues of racism and blackface in America. They won’t just make offensive content and choices disappear. They want to bring them out into the open so that society knows that it’s time to confront blackface and racism. Just like I knew it was time to confront my own past.

I spent an hour composing a text before sending it to my friend. To my surprise, not only did they immediately respond, but they wanted to talk more about it. They expressed their remorse for what they had done. They were horrified at what they had participated in. They rained apologies on me. They sent me walls of text almost as long as Gone With the Wind itself.

Out of everything they said, the words that affected me most were: “I know if someone had a conversation with me then I would’ve listened? Why didn’t someone talk to me?” I was going to sugarcoat the answer before I thought better of it. I picked up my phone and told my friend “It wasn’t safe to speak.”

I thought back to that Halloween party. When I saw my friend in blackface, I immediately turned to other people as if to ask “Are you seeing this too?” If anyone else noticed and were bothered by it, they stayed silent.

At that moment, it felt like I was completely and utterly alone. I thought I was the only one feeling pain about my friend’s blackface. I thought if I spoke up, no one would support me. In fact, they might make me the villain of the party for ruining the mood. I might be forced to leave. Or something worse could happen. I only felt safe in silence. So I said nothing.

If I had felt safe expressing my opinion at the party back then, maybe I could’ve avoided having to avoid talking about blackface. This article definitely would’ve been a lot shorter. It would’ve ended with “And then we told my friend to go home.” But unfortunately, we can’t change the painful past. There’s no undoing what my friend did, and how I felt about it.

What’s changed for me is that I know that I can seriously talk about the blackface incident with my friend. If they just said sorry, and nothing more, then the conversation would be over. The door would be closed. And the next time I felt my stomach churn at the mention of blackface I would have to move on in silence. Luckily, my friend has committed to listening and learning and hopefully growing from this experience. When I told them I’d be writing about all of this in an article format, hey supported me. They encouraged me to speak out and be truthful about what hurts.

Shows like 30 Rock and It’s Always Sunny can take down as many episodes as they want. But in doing so, they have removed a chance for them to have a meaningful conversation. On the other hand, the decisions involving Gone With the Wind and Mad Men have created opportunities to confront issues of blackface and racism. Of course, this is far from a perfect solution.

We can’t cure the virus of blackface overnight. If we want a real shot at eliminating it, we have to figure out how to turn Hollywood into a space where this virus can no longer thrive. We also have to figure out how to make it so people of color don’t worry about what they’ll see when they walk into a Halloween party. Making those changes starts with honest conversations.

If you’re a creator who has blackface in your past, I know it’s not easy to have this conversation. Because I’ve been on the other side. I’ve literally stared into blackface and couldn’t talk about it for years. And in the end, I had to take a risk just to get a shot at healing.

Although I accept what I had to do in order to move forward, I wished it could’ve been different—that the pressure to have the conversation didn’t fall on me. But if you’re a creator who used blackface, you can ease the burden. Not by making your past disappear, but using it to open up a conversation about why it’s wrong, the harm it causes, and how we can work to eliminate the practice completely. Again, I know it won’t be easy. But take it from someone who is having an honest, hard, and overdue conversation about blackface:

Inviting people of color to talk about their pain can make a difference.

It did for me.

Andrew Tejada is an NYC native so there’s a 90 percent chance this was written on the subway. When he’s not writing or consuming movies/tv, he’s pitching his Static Shock screenplay to anyone who’ll listen. More of Andrew’s projects and words can be found on Facebook at “Arete Writes Things.”